The Leftovers Project: Tackling Food Insecurity at James Madison University

Soaring tuition costs, increasing loan rates, and dwindling government grant opportunities

are making it hard for many college students to afford basic living necessities. In 2023,

the National Library of Medicine reported that an alarming 19% - 56% of students (depending

on the specific college or university) were food insecure, meaning they lacked the nutrition

needed for a healthy and active lifestyle.

James Madison University (JMU) in Harrisonburg, Virginia sits in the middle of that range,

with 39% of its student population experiencing food insecurity. The good news is that JMU’s

dining halls always have leftovers, and a donation program allows students to donate food from

their meal plan to students who need a meal. Putting leftovers together with the students that

need food would be a simple, neat answer to a big problem.

The bad news is that student food insecurity exists inside a complex system of food distribution,

so solving it at JMU and other colleges and universities is anything but simple. Investigating

issues inside complex systems is what students in JMU’s Integrated Science and Technology (ISAT)

program learn to do using a system dynamics approach and Stella.

Defining a project scope

ISAT students take Introduction to Systems Thinking to learn how to apply modeling and simulation

to their area of focus: biotechnology, computing, energy, the environment, industrial

manufacturing, or public interest issues. In their junior and senior years, they take the Capstone

Experience classes, a two-year endeavor to study and model a real-world problem. The experience

culminates in a presentation at the College of Integrated Science and Engineering Senior

Symposium. It was during the first Capstone Experience class that Dr Raafat Zaini, Assistant

Professor, visited as a guest lecturer to give a project pitch to potential students.

In 2023, Dr. Zaini visited the first capstone class to deliver a lecture. "I pitched the capstone

project idea of looking at food waste and the possibility of sharing food with people who need it,"

says Zaini. Lorelai Lamoureux, a student in that class, was immediately interested. "Food has always

been important in my family. It’s a way of connecting with friends, family, and the local community,"

she says. "I recruited Isaiah Martinez and Raleigh Mann to work on the project with me and we asked

Dr. Zaini to be our advisor. He suggested we attend a regional conference on food waste which

featured a speaker from the JMU food pantry."

Lorelai Lamoureux, Isaiah Martinez, and Raleigh Mann

Lorelai Lamoureux, Isaiah Martinez, and Raleigh Mann

Through that conference, the team understood the scope of the general food insecurity problem

and decided to narrow their focus to their own campus. "Limiting our scope was an important

step," says Mann. "The greater food system includes humans, animal and vegetable production,

waste streams, and more. By focusing on the JMU campus, we had the right level of complexity

and were able to whittle down the problems."

Collecting data and building a model structure

The project started with a stakeholder analysis. "We wanted to know who had access to JMU data

and who makes decisions about how leftover food gets used," says Martinez. "We couldn’t get good

information about waste or leftovers. So, we started volunteering in the dining hall. Over a

number of weeks, we learned about how the dining hall worked and were able to collect some

actual data."

Still, data collection was a challenge. "In our weekly project meetings, there was the feeling

of a data crisis," says Zaini. "I reminded the students that models are not built of numerical

data and encouraged them to build a system structure that would reveal the questions they needed

to answer to find solutions."

While their focus was limited to the JMU campus, the students were still investigating a complex

system. It includes campus administration, a third-party dining hall vendor, multiple dining halls,

rules and regulations that guide food access and leftover distribution, a food pantry, and

thousands of students with a range of nutritional needs.

Most students access on-campus food through a pre-paid meal plan. When they enter the dining hall

and swipe their student id, a meal is deducted from their allotment. Students on the meal plan

are allowed to donate up to two meals (swipes) per day.

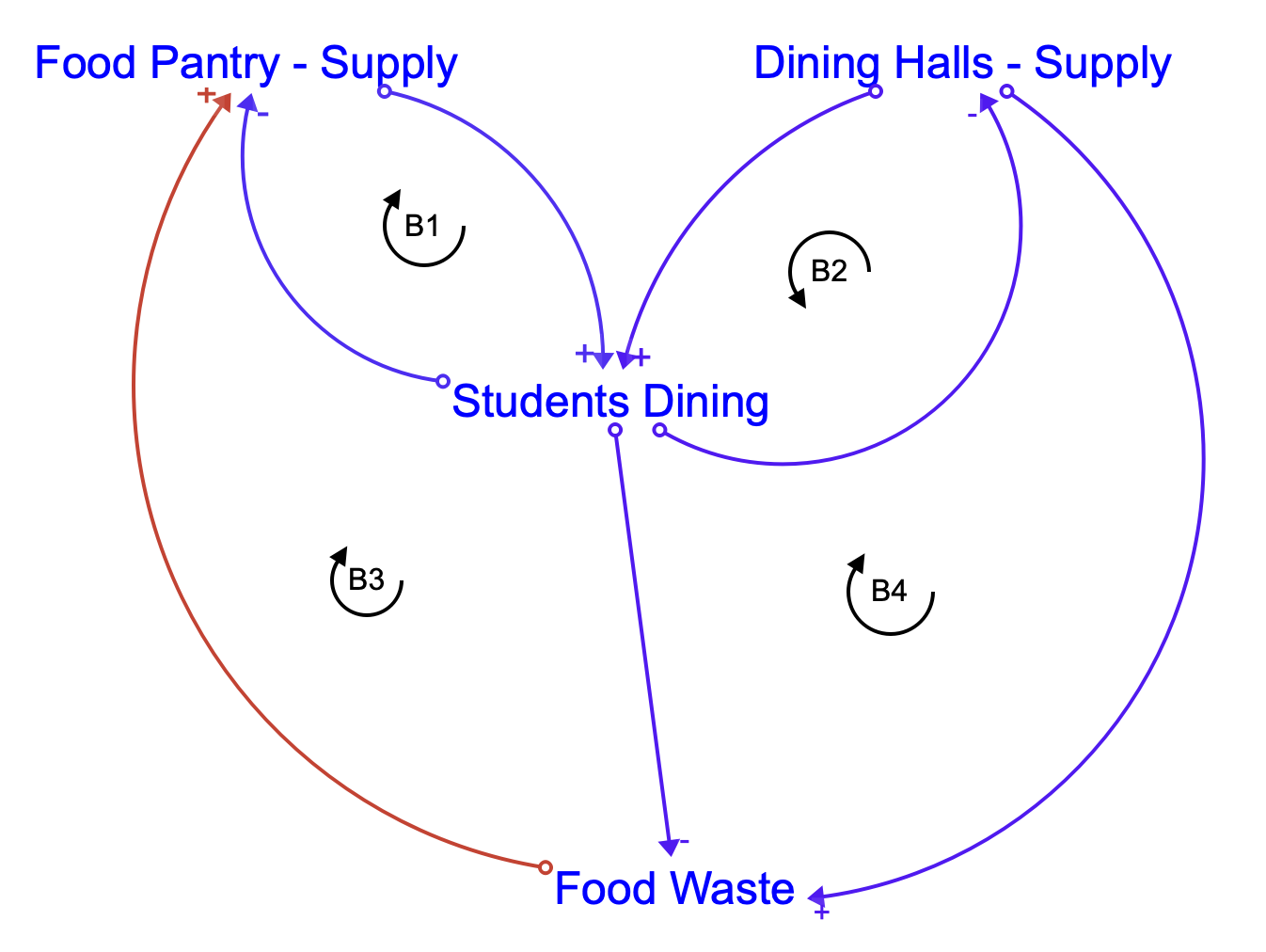

Lamoureux, Mann, and Martinez used what they learned about JMU’s food system to develop a

conceptual framework. It has three feedback loops that include students, dining halls, an

existing student food pantry, and food waste.

Conceptual framework with feedback loops

Conceptual framework with feedback loops

B1 relates students dining on campus and the JMU Food Pantry food supply. The more students

use the pantry, the more food the pantry serves. Conversely, the pantry can only serve the

food it has. When the pantry has less food, fewer students are served.

B2 relates the dining hall’s food supply to students. The more food students demand from

the dining halls leads to decreases in their supply. With less food in the dining hall

supply, fewer students can be served.

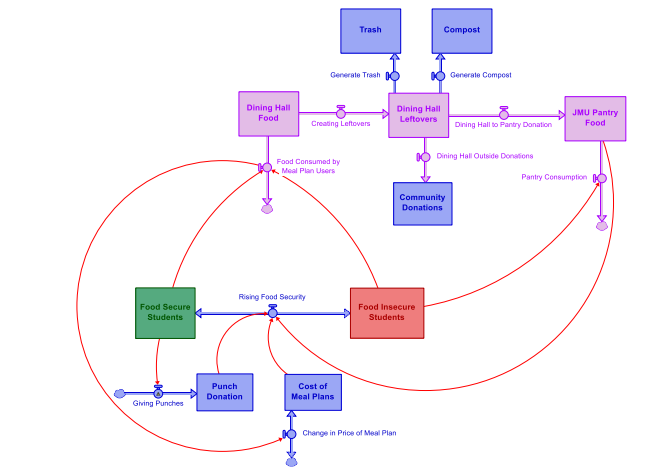

The framework served as a basis for the model, which includes both the movement of food

and students through the system. Food is accessed through dining halls and the food

pantry, donated to community organizations, thrown away, or composted. Students access

food and move in and out of food insecurity.

Since students rarely consume all food produced, there is waste, and the red connector

illustrates a pathway for food supply that did not previously exist. B3 illustrates

that food waste is available for the Food Pantry should policy allow, and creates an

outlet for food waste that was previously only accumulating (before the red connector

was added).

B4 relates the students dining on campus with the dining halls supply, the amount of food

waste produced and the JMU Food Pantry Supply. With more food waste produced from the dining

hall supply, more food has the potential to be donated to the food pantry which allows for

more students to be helped. However, this still creates a balancing loop as less students may

attend the dining halls which would lead to less food waste being produced from the dining

hall supply leading to less donations shared with the Food Pantry.

Top level feedback structure of JMU food distribution system

Top level feedback structure of JMU food distribution system

Evaluating the effectiveness of policy changes on food insecurity

Using the model, students simulated the flow of donations into the pantry and to students,

as well as student engagement in meal donation programs. JMU is currently experiencing student

population growth, so the model assumes increases in food production and in the number of food

insecure students. Through simulations, the team looked for a scenario that supported student

population growth and curbed both student food insecurity and food waste.

Sensitivity analyses measured the impact of changes to these parameters:

- Increases in donation rates from the dining hall to the food pantry

- Increases in allowed meal plan voucher donations (currently limited to two/day/student)

- Increases in the proportion of students who are willing to donate from their meal plan

- Increases in the number of students willing to access food through the pantry

- Decreases in the number of food insecure students

Findings suggested that simply raising the amount of dining hall food available to students

via the pantry would have an insignificant impact on student food insecurity. Increased

student awareness and willingness to donate food had a greater positive impact, as did an

increase in the number of students willing to access food through the pantry.

Policies guiding the use of dining hall and meal voucher donations to the food pantry were

also evaluated. Currently, the JMU Community Engagement and Volunteer Center (CEVC) operates

the university’s Food Recovery Network, which is a chapter of a national program. The Food

Recovery Network collects leftover dining hall food from the previous week. If more than 12

meals are collected, that food is donated to the Salvation Army. Food that makes up fewer

than 12 meals is donated to the JMU Food Pantry. Leftovers from self-serve stations must be

composted. Other policies affect food drop-off locations and current practices for publicizing

Food Pantry access.

Various policies—including increasing collaboration between dining halls and the JMU food

pantry, instituting a pantry awareness campaign, increasing willingness of students to donate

swipes, and increasing the amount of salvageable food served in dining halls—each decreased

the number of food insecure students by 6% - 8.5%. Food waste also decreased.

The greatest positive impact came when multiple policy changes were enacted. A Full JMU Pantry

Utilization solution simulated donations of all salvageable leftovers from both dining halls and

running an ongoing pantry awareness campaign to destigmatize usage and inspire student donations.

Together, those changes could reduce food security rates by at least 20%.

"A system dynamics approach using Stella allowed us to test the multiple resources that are

available as food insecurity solutions," says Martinez.

Learning through modeling

Students weren’t surprised that student food insecurity on the JMU campus couldn’t be solved

with the flick of one switch. "One of our professors, Rod McDonald, says ‘you don’t need a

silver bullet, you need silver buckshot,’" says Martinez. However, model building and simulation

did unlock insights.

"We began building the model with one dining hall and then added a second," says Martinez. "In

the course of making that change, we asked about getting food from one dining hall to the

other and were told that moving food would require a car and a key fob and overcoming other

logistics. In fact, the dining halls are a short walk apart. Food could be moved between them

in a grocery cart. It seems like a small thing but by asking questions raised by modeling, we

overcame the speed bump."

More surprising was how little food was donated. "Lorelai and Isaiah reported only about 12 Ziploc

bags of food went to the Salvation Army each day," says Zaini. "Just that from huge dining halls?"

"We did learn that the dining hall kitchen team is interested in minimizing food waste through

measures like using today’s leftover rice for tomorrow’s soup," says Martinez. "While we were

surprised by the low volume of leftovers, we saw that if both dining halls minimized waste,

it would have a positive impact."

"Given policies around food recovery, there is less food available to the pantry than we thought

there would be." says Lamoureux. "An important question that came out of simulation was if

donations could prioritize both students and community organizations so that the CEVC’s

mission of serving both could be preserved."

Why learn System Dynamics? Why learn to apply System Dynamics with Stella?

"System dynamics shows what anecdotes and data can’t show," says Mann. "By building a model,

you can see how a change in one part of the model cascades through the system. In the Leftovers

Project, for example, we saw that increasing the number of meals a student can donate each day

would change the number of food insecure students helped from tens to thousands."

"Stella is a fantastic communications tool and the barrier to entry is low," says Martinez. "With

no math or technical experience, you can build and explain a system that includes expertise to

people with no modeling experience. And, it gives everyone involved a common language for

collaboration and understanding."

"I learned to use three system dynamics software applications in graduate school," says Zaini.

"I keep using Stella because of its killer feature, storytelling. Storytelling allows groups

to simulate, learn, add to the model, simulate, learn, add to the model."

Storytelling also made it easy for the students to create slides and posters to present their

work. "Stella makes models that present well and trigger feedback," says Mann.

Presenting and using the model

Lamoureux, Martinez, and Mann presented their model and findings at the College of Integrated

Science and Engineering (CISE) Senior Symposium in the spring of 2025. They also presented at the

2025 Student Sustainability Summit at Bridgewater College and during the poster session of the 2025

International System Dynamics Conference in Boston, Massachusetts. "People reached out after each

presentation," says Martinez. "We continue to push for the model to be used by stakeholders."

Martinez, Mann and Lamoureux have all graduated from JMU and the ISAT program and moved on to

employment and graduate education. Their model, however, is not sitting on a shelf. "The Leftovers

Project is just the beginning in our understanding of the student food insecurity and waste problem

and possible solutions," says Zaini.